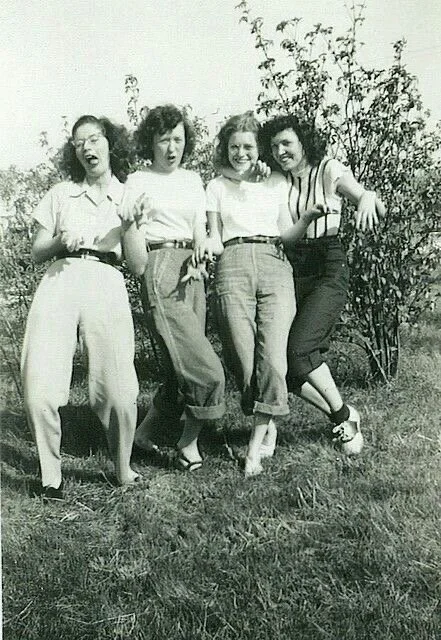

II. The Pedestal & the Cage

The Southern Woman’s Double Bind

Southern womanhood was carved out of contradictions. From the whitewashed porches of plantations to the weathered log cabins tucked deep in the hills, women were exalted as the moral heart of the South — pure, pious, and enduring. They were lifted high as “ladies,” symbols of honor so elevated, yet with expectations that made it difficult to breathe.

The pedestals they were placed upon also served as a cage, since being cherished also meant being controlled. To be protected was to be compliant. The very qualities praised in women — modesty, obedience, self-sacrifice — became shackles that bound them to narrowly limiting roles. What social psychologists refer to as ambivalent sexism ruled their place in the world: adored when submissive, despised when defiant. A woman could be praised as an angel one day then scolded as a harlot the next, her reputation hanging on a glance, a whisper, and her ability to fall in line.

Needless to say, the myth of the “Southern belle” was more than poetic nuance; it was politics. Her supposed fragility became the driving force for upholding racial terror. Lynchings were carried out in her name, as her purity was the justification for unspeakable violence. Yet when women themselves were harmed, they were often blamed — told they had tempted men, provoked wrath, or failed to remain pure. Reverence and repression worked hand in hand, polishing the pedestal while tightening the chains around the cage.

The masculine culture of honor, and the heavy burdens that came with it, deepened the bind. In the South where insults to manhood demanded violent redress, a woman’s body became the battlefield. Her silence, her chastity, her willingness to smile and nod, were not merely personal virtues; they also served as symbols of the family reputations that were to be defended at all costs. A husband’s pride, a brother’s rage, a father’s honor — all could be measured in the behavior of a daughter, a sister, a wife. Her worth was currency and her life the collateral.

And yet, beneath the glory of purity, many women carried another truth that told them, reverence and repression were twins, and both could leave an ugly wound. As mothers came to understand this, they were led to pass down their knowledge to their daughters in whispers, explaining how to nod without actually agreeing, how to survive and soften a man’s rage, and how to keep secrets safe behind their lowered eyes.

Yet as time carried on, repression grew exhausting, and naturally, women found ways to push back. Some resisted openly, stepping into the risky light of suffrage halls, classrooms, and reform movements. Others carved out subtler paths by wielding their influence in unseen ways — shaping loyalties, preserving dignity, and passing down how they learned survival and endurance.

Black women, bound by both racism and sexism, forged resilience through unbreakable community bonds. They built schools, led churches, and sustained networks of care that became sanctuaries of both survival and defiance. White women sometimes subverted their pedestals — even using their supposed fragility as cover to shield the most vulnerable and resist brutality. Small acts of defiance, whispered plans, and silent strategies were their weapons, unrecorded but no less true. And paradoxically, the women who chose to resist unconditional compliance, are those who have also played a huge role in keeping our society moving forward, even when their lifetime achievements went unnoticed.

To be a Southern woman was to live in the crossfire of adoration and accusation, worship and blame. But it was also to inherit the fierce creativity of those who endured — who found ways to survive even when the odds were against them. Their legacy serves not only as the burden of the cage, but also as the quiet rebellion that allowed future generations to break free, once and for all.

photo credit: Pinterest