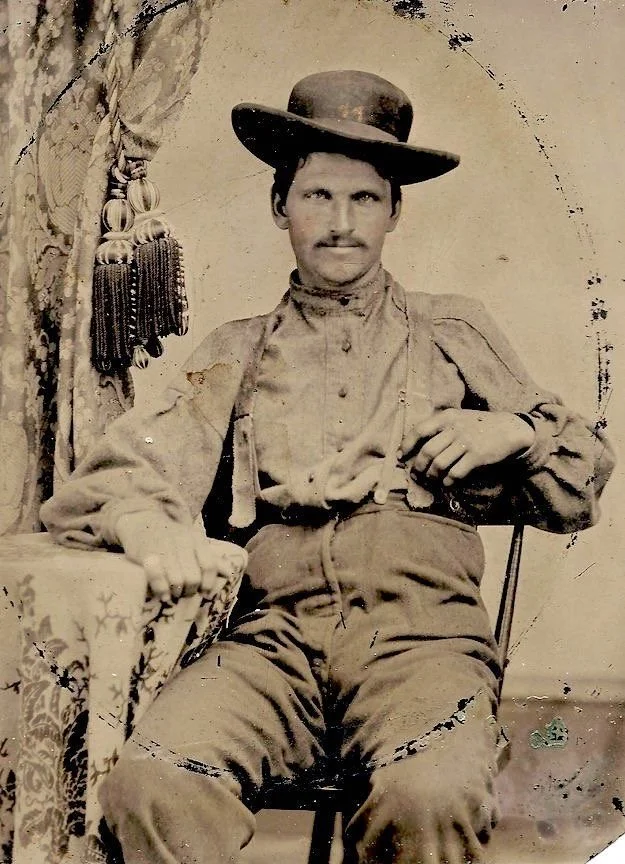

George William Gray

Not actually George Gray

Certain details have been embellished for the purpose of the story, but the basis of information comes from their true life experiences.

For George W. Gray, life both opened and closed in tragedy. He came into the world in 1860, on the eve of a nation’s unraveling. A year later, the Civil War thundered to life. After the Battle of Bull Run, the Confederacy swelled with confidence, leaving some men emboldened, others paralyzed by dread. Among the emboldened was George’s father, and in April of 1862, he left his young family to join the Confederate ranks.

Before the war, George’s father had been a store owner near Flat Rock, Virginia—known for his fairness and congeniality, he was liked by neighbors and patrons alike. He had married his childhood love, Mary, and settled into a life that seemed steady, almost charmed. But Fort Sumter’s attack cracked that stability. The air filled with restless voices and clamor, the sound of peace dissolving into chaos.

A few months after her husband’s departure, Mary discovered she was with child. She delivered a daughter six months before his expected return. But that return never came. George was barely three years old, his sister still in swaddling, when the letter arrived that sent his mother to her knees. His father had been wounded in battle and carried to a hospital, where he died of pneumonia.

Mary collapsed into grief so consuming it hollowed her days. Often she lay confined to her room, curtains drawn, her children left to the shadows of her sorrow. The townspeople also mourned, grieving the neighbor and storekeeper they had admired. Out of pity and reverence, they gathered around Mary and her children, their kindness cushioning young George. Wrapped in their compassion, he felt a peculiar glow of love and importance, assuming that warmth might follow him through life.

By eight, George had adopted the role of his mother’s caretaker. He also learned the store’s rhythms, the chores of the household, and tending to his mother’s fragile heart. He called himself “the man of the house,” though he couldn’t yet grasp the full weight of those words. Pride swelled in young George as he felt accomplished for stepping up to care for his mother and baby sister. Then, everything changed.

One strange afternoon, Mary announced to George and his sister that she had met a man named Randall, and he had asked to marry her. After hearing the news, George’s heart cracked. He felt hurt and betrayed, but also confused why his mother would do this to him. His feelings were too hard to explain. The pain hit a little deeper when George found out his mother was going to sell the store and they would be leaving Flat Rock to live in Surry, Virginia on Randall’s peanut farm. To George, this was exile—leaving behind the only life and love he’d ever known. And for peanuts.

As for Randall, he proved to be a hard man: overbearing, sharp-tempered, fond of liquor, and with a hunger for control. He belittled George with cruelty unfamiliar to the boy, who had only known the gentleness of his mother. Randall often called him “sissy-boy” or by the name Georgianna. He scolded him out in the fields when he showed little initiative for learning life on the farm.

As George became a young man, their clashes grew increasingly violent. As Randall became more and more threatened by George’s growing strength, he turned to other tactics, like slander, to humiliate George around town so he would want to pack up and leave.

In the end, that’s what he was left to do. When his mother turned from him, saying things would better this way, he learned that love could be bargained away, and family bonds could be severed as if nothing but a piece of string.

Adulthood

George was twenty when he left home. With little more than the clothes on his back, he left town carrying both bitterness and a restless hunger he didn’t know how to feed.

The road south took him to Norfolk, a city bustling with ships, markets, and rough company. There, half-starved and without direction, he thought of an old friend—a man who had settled into the steadier life of farming. When George appeared staggering down his road, his friend offered what little he could: a cot in the loft above the barn and steady work on his peanut farm. George was grateful, and noticed how much easier it was to farm when Randall wasn’t around, and when he made money doing it.

George had never earned wages before, and the feel of coins in his pocket at the end of each week struck him like a revelation. Money gave him a taste of independence and fresh ideas for the future he’d carve out for himself. But more dangerously, it bought him a ticket to risky indulgence.

Nights in Norfolk taverns introduced George to poker games. At first, he played small—pennies tossed on the table, and the thrill of a good hand sending a jolt through his blood. But when he won, when the pot spilled his way, a completely new being came to life. The world exploded with possibility, turning every day before that one into a meaningless memory.

His friend on the farm noticed the change and warned George about the men he was keeping company with. He knew they had reputations for being drifters and tricksters; men whose names carried no weight in town except as caution. George only laughed, brushing off the concern. After all, he liked their sharp talk, their wild and reckless stories, and the way they made him feel part of a secret world. To him, they seemed harmless, even clever. And they played cards well.

By the time George turned twenty-five, the card tables had become his second home. The farm work kept his hands busy by day, but it was the nights—the smoke-filled rooms, the clink of coins, the flick of cards—that made him feel alive. He had grown sharper with every hand, learning not just the games, but the men who played them.

That’s when he met Jesse Key. A man with money, swagger, and a taste for the thrill of poker. George had seen him about town, strutting as though fortune itself had chosen him. But George had noticed something else too: the quiet servant girl who trailed Jesse’s household errands, head bowed, eyes shadowed. Her name was Roany. She moved like someone carrying a burden too heavy for her young shoulders.

George was intrigued by her. She mirrored back to him the same loneliness that he had used poker and liquor to suppress. He recognized the resignation in her eyes, the look of powerlessness, like someone caught in a world she couldn’t escape. The more he saw her around town, the more he convinced himself that he could save her from the empty life of servanthood by making her his wife. Then came a cold night in January when George got lucky, and the opportunity to claim Roany fell right in his lap.

The men were playing cards, and Jesse was dealt the kind of hand men dream of—a sure winner, cards so strong they practically glittered. But when George’s cards hit the table, Jesse’s grin faltered. Somehow, impossibly, George’s hand topped his.

Jesse was on the verge of losing much more than he could afford, and George knew it. George couldn’t help but feel a little sorry for Jesse, the man who had been a tower of strength a short time ago, who now seemed to be nothing more than a lost puppy. Perhaps George allowed his pity to serve in getting him what he wanted. He offered Jesse a deal to save him from his crippling debt in exchange for Roany. Eager to seize the lifeline, Jesse accepted without giving a second thought to the impact it would have on his wife or the household. And certainly without giving a thought to Roany.

When Roany heard news of the arrangement, reality served her another cold, hard reminder: she was invisible to the eyes of love. She was a transaction between men—shifted from one master to another under a thin disguise of marriage. For Jesse, the arrangement solved his immediate debt, and for George, it was a way to prove to himself that he could command fate and fortune with his brilliant ideas alone.

Relevant Records:

Newspaper article of Confederate victory